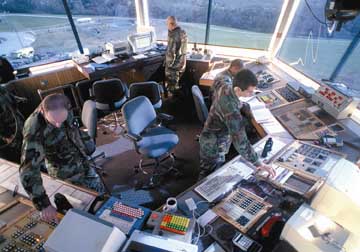

Mike Hilliard. [Source: Mary Schwalm / North Andover Eagle-Tribune] | The air traffic control tower at Logan International Airport in Boston is called by the FAA's Boston Center and told that communication with Flight 11 has been lost, but when the tower supervisor looks at the plane through his binoculars, he can see nothing outwardly wrong with it. [North Andover Eagle-Tribune, 9/6/2011; CNHI News Service, 9/9/2011] Flight 11 took off from Logan Airport at 7:59 a.m. (see (7:59 a.m.) September 11, 2001). It was in communication with the Logan control tower before being passed on to the FAA's Boston Center. All communications between the Logan tower and Flight 11 were routine, and tower operators received no indication that anything was wrong with the flight. [Boston Globe, 9/12/2001; Federal Aviation Administration, 9/17/2001 pdf file; New York Times, 10/16/2001] But since the Boston Center instructed it to ascend to 35,000 feet, just before 8:14 a.m. (see 8:13 a.m. September 11, 2001), Flight 11 has failed to respond to all air traffic controller communications (see 8:14 a.m.-8:24 a.m. September 11, 2001). [Federal Aviation Administration, 9/17/2001 pdf file; New York Times, 10/16/2001; 9/11 Commission, 8/26/2004, pp. 7] Tower Supervisor Sees Nothing Wrong with Flight 11 - The Boston Center now calls the Logan tower to alert it to the problem. "We got a call in the tower that communication with the plane had been lost," Mike Hilliard, the tower supervisor, will later recall. |

Then, Hilliard will say, the radar room, which is on a level below the tower room, "called and asked if we could still see the plane." Hilliard looks at the radar screen and can see Flight 11's track. He then grabs his binoculars, looks out the window through them, and can see Flight 11, because the sun is reflecting off its aluminum fuselage. The aircraft is flying "at 15,000 feet, and he wasn't trailing vapor or smoke," Hilliard will recall. Hilliard therefore informs the radar room that he cannot see anything wrong with the plane. Assistant Says, 'I Hope It's Not a Hijack' - One of Hilliard's assistants then says to the supervisor, "I hope it's not a hijack." This gives Hilliard an uneasy feeling. He replies, "It better not be, because if they got the airplane that quick, it's a team that took the airplane." He says to his assistant that the problem with Flight 11 has "got to be mechanical," and then adds, "Nobody can get a plane that quick." [North Andover Eagle-Tribune, 9/6/2011; CNHI News Service, 9/9/2011] The 9/11 Commission will conclude that Flight 11 is hijacked at around 8:14 a.m. (see 8:14 a.m. September 11, 2001). Flight 175, the second plane to crash into the World Trade Center, takes off from Logan Airport at 8:14 a.m. (see 8:14 a.m. September 11, 2001). [9/11 Commission, 7/24/2004, pp. 4, 7] |